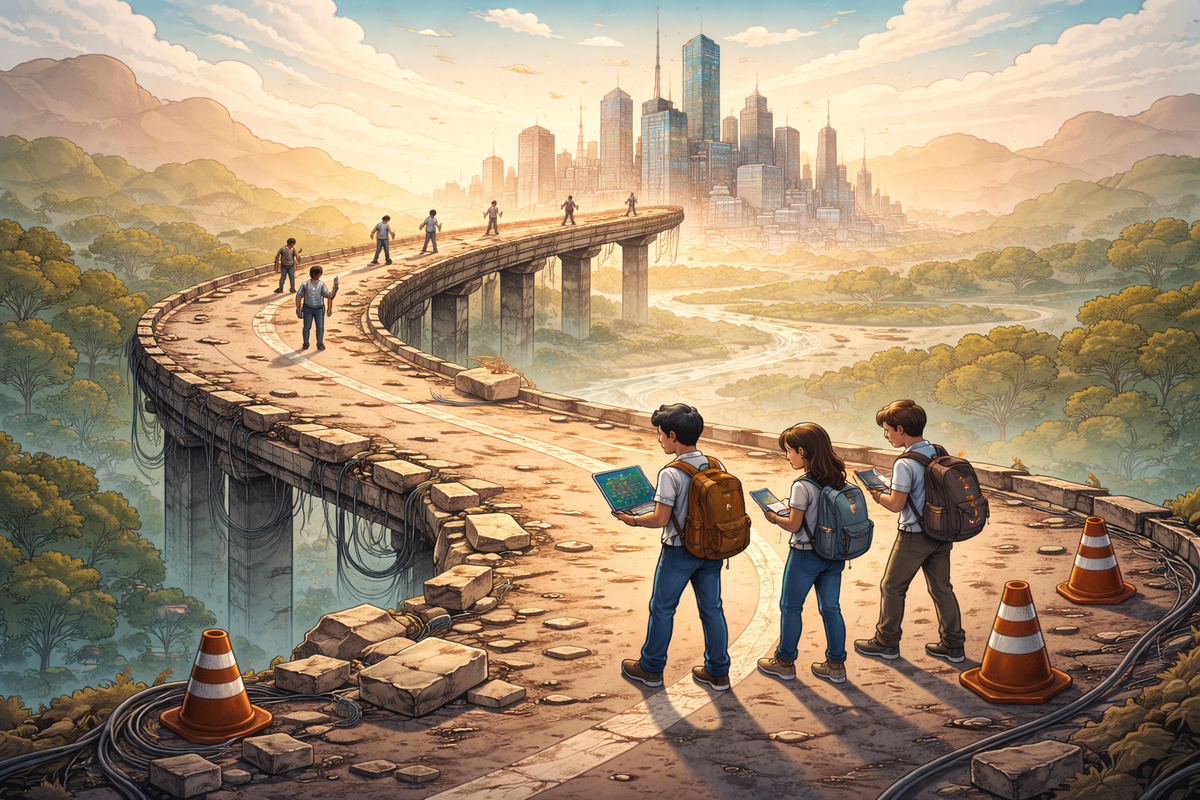

The Broken Onramp

The onramp into technology is no longer forgiving. Junior engineers arrive more capable than ever, yet face fewer openings, thinner support, and higher expectations. This essay examines how the system changed, why potential is being wasted, and how to remain in motion inside a hostile structure.

I am often asked by students and early career engineers whether it still makes sense to enter the technology industry. The question usually comes hesitantly, sometimes framed as a request for permission rather than advice. That hesitation is understandable. The profession has changed, and many of the assumptions that once guided entry into it no longer hold.

When I started, the industry was looser, more forgiving, and structurally incomplete. Formal credentials mattered less, partly because the work itself was still being figured out. I did not enter with a computer science degree. What I had instead was proximity to systems, curiosity about how they failed, and an opportunity to learn inside environments that assumed beginners would be unfinished.

That assumption has largely disappeared.

In the earlier phase of the industry, the onramp was wide. Companies expected junior engineers to arrive without polish and invested accordingly. What mattered was not readiness, but trajectory. The system tolerated inefficiency because it understood learning as a necessary cost of production.

A familiar initiation ritual from that era still repeats itself today, though with less patience around it. A junior engineer joins a team shortly before a major release. There is a deadline, a client, and a system that has already accreted complexity. The newcomer is assigned small fixes, low risk tasks, or support work. On paper, nothing critical.

Then launch night arrives.

The system behaves differently under real load. Assumptions collapse. Latent defects surface. Configuration mismatches, dependency conflicts, and environment specific failures appear in rapid succession. Senior engineers switch from design mode to containment mode. Logs scroll endlessly. Someone edits a configuration directly on a production server because there is no time to do it properly.

This moment is rarely graceful. It is noisy, exhausting, and vaguely unethical by the standards of any engineering handbook. Yet it is also where junior engineers learn what the profession actually entails. Not abstraction, but consequence. Not correctness, but responsibility.

What matters in those moments is not who introduced the defect. It is how the team responds, whether knowledge is shared or hoarded, and whether failure is treated as a teacher or a liability. In healthier systems, the lesson is made explicit. Fixing the issue is necessary. Understanding why it happened is essential. And finding a way to stay curious, even under pressure, is what allows people to last.

Early careers are shaped less by formal instruction than by proximity to these moments. They are also shaped by whether someone chooses to explain what is happening, or merely expects the newcomer to absorb it by osmosis.

Over time, I was fortunate to work with people who treated learning as part of the job rather than a private burden. As my own responsibilities grew, I tried to replicate that behavior. I mentored junior engineers. I helped design internship programs. I watched new cohorts arrive with technical capabilities that far exceeded what I had at the same stage.

And increasingly, I watched the system fail to absorb them.

The environment junior engineers enter today is fundamentally different. The number of qualified candidates far exceeds the number of entry points. Degrees, bootcamps, and certification programs produce a constant supply of talent, while organizations quietly reduce their tolerance for onboarding costs. Entry level roles are contested not only by peers, but by displaced mid level engineers, by offshore labor markets, and by senior practitioners augmented by generative tools.

The paradox is striking. Many early career engineers today are better prepared than previous generations. They understand testing, version control, deployment pipelines, and cloud infrastructure before their first full time role. I have seen interns architect and deploy production systems that delivered real value. Some of them still did not receive offers, not because they failed, but because the system had no available slot for them.

Even when junior engineers are hired, the margin for error is thinner. Support structures are weaker. The implicit contract has shifted. The expectation is no longer growth over time, but immediate contribution. Variance is treated as inefficiency. Potential is evaluated as risk.

This is not a moral failing of individuals. It is an emergent property of a system optimized for short term output.

It has become difficult to ignore, especially when viewed through a generational lens. I watch younger people encounter the profession with more skill and less opportunity than those who came before them. The result feels less like competition and more like waste.

So rather than offering reassurance, I prefer to offer strategies that acknowledge the structure as it is.

The first is to be honest with yourself. If you are drawn to this work because you enjoy understanding systems, solving ambiguous problems, or building things that persist beyond you, then the difficulty is not a reason to stop. Difficulty does not negate meaning. But if you are here because of external expectations, lifestyle narratives, or outdated promises of effortless reward, it is worth reconsidering. A career built against your own disposition rarely becomes generous with time.

The second is to cultivate visible eminence. Not self curated portfolios, but work that exists within systems you do not control. Contribute to open source projects where acceptance is not guaranteed. Build software for institutions, communities, or organizations that already exist. Teach. Present. Participate. These signals matter because they are conferred, not claimed.

Internships remain one of the few reliable onramps, imperfect as they are. If you secure one, treat it as an opportunity to demonstrate judgment and reliability, not brilliance. If you do not, compensate deliberately. Prepare for interviews until the format itself no longer consumes attention. Apply broadly, including to non technology companies. Technical roles exist in many places that do not describe themselves as tech.

If direct software roles remain inaccessible, consider adjacent ones. Quality engineering, data work, infrastructure, operations, developer support. These roles sit near the core and can be traversed over time. Lateral movement is not failure. It is a way of staying in motion.

Finally, remain flexible. Geography, contract work, partnerships, independent projects. Systems reward those who can change shape without losing coherence. Rigidity feels principled, but it is often just brittle.

None of this guarantees success. Anyone who promises certainty in the current environment is selling comfort, not truth. But these approaches increase surface area. They create optionality. They allow movement while the system continues to rearrange itself.

The technology industry still likes to describe itself as meritocratic. In reality, it behaves like any complex system. It amplifies certain signals, suppresses others, and periodically discards value through misalignment.

Understanding that does not make the situation fair.

But it does make it navigable.

And sometimes, that is enough to keep going.